Literacy Improvement Series~ Vocabulary: When and How

Welcome back! Or just welcome!

This is the second installment of my Literacy Improvement Blog Mini-series. (That sounds so official, like it will be airing on Netflix or something. I’m just hoping it is helpful.)

Today’s topic: Vocabulary: When and How

Remember a few years ago when frontloading was the buzzword? We would talk about important vocabulary words before reading a book. Or we would have our EL teacher pull students before beginning a unit and have her work with the kids on certain pertinent terms we would be using throughout the next few weeks. I tried to remember to do that.

Well, now I teach for biliteracy. I can’t just “try” anymore. Vocabulary instruction is the center of my universe! The language must be accessible to all my students regardless of their language proficiency, and they must have context. You guessed it, another shift had to occur in my planning and instruction.

One ah ha! for me was shifting when I do my first read aloud related to a unit. Before teaching for biliteracy, I would often use a read aloud as an introduction to a unit. What I didn’t realize then is that those texts became a moment to check out for my ELs. The vocabulary, whether the text was fiction or nonfiction, was often incomprehensible. Words they had never heard. The pictures in the texts help, but they can only go so far. My “frontloading” was often more discussion about what words meant. Sometimes I would have a visual and sometimes I would simply provide context. It wasn’t enough.

Now I never introduce a unit with a text. Instead, we have an experience.

I often set the context of the learning with a shared experience. It may be realia. It may be a concept attainment through guided sorting (see Teaching for Biliteracy p. 52-56, 81-82). And it always includes Total Physical Response (TPR), where my students practice with vocabulary using gestures, visuals, and spoken language to understand terms important to the unit.

TPR is the one strategy that has lent to more vocabulary understanding than any other strategy I have used with my students. It takes planning and preparation, but the payoff is tremendous.

When planning for our units, I start with our standards then develop content and language targets and an essential question. From there, I decide on the pertinent vocabulary that my students need to be able to comprehend and use in order to accomplish those goals.

This vocabulary then becomes incorporated into TPR. In the TPR, I typically create a flipchart (or Powerpoint) including the words in context in a complete sentence, a visual, and I plan for a gesture to accompany each term. When introducing the compiled TPR to my students, there is a very intentional gradual release of responsibility. This gradual release occurs over the length of the entire unit of study.

Progression:

- Student voices off. I speak and gesture while showing visual and print word. Students copy gesture.

This sample is taken from one of the pages of my kindergarten push/pull TPR. The small text at the bottom is my reminder of the gestures we do on this page.

- Students echo words and gestures while I show visuals. (Sometimes this takes several class sessions, depending on the group and the complexity of the vocabulary.) Check out my first graders on their second day of the Producer and Consumer TPR.

- Students and I “chant” TPR as one voice, everyone speaking together as visuals and print words prompt. (This usually takes quite a few class sessions for students to become confident. This is also where you can begin to see which students are still at the “gesture only” stage and need more time to practice the oral production.)

- Student leaders take over as “teachers”, guiding the class through the gestures and pointing to the print words. I step back and help individuals as needed while still chanting along.

- I “take a break and relax” (as I tell my students) and let them go. Student volunteers lead the class and point to the words. I am no longer needed to “coach” at this point, except in special circumstances. See a kindergarten video sample of this.

- Students “quiz” each other in Thinking Partners. One partner will have his/her back to the interactive whiteboard while the one facing will gesture based off of the visual and print word(s) on the screen. The student who cannot see the board produces the spoken terms that coincide with the “clues” their partner gave them.

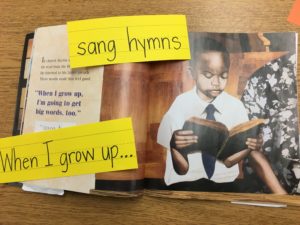

- TPR is then taken to reading and writing. Students take a differentiated, printed version of the TPR (some with blank spaces, some directly taken from TPR) and put it in order in a book, matching clues with visuals and adding details as needed. When appropriate, we extend the TPR to add information we learned during the unit.

Here a student is matching the TPR sentences to the visual. This will result in a book that he can read independently.

At the end of our Living and Nonliving unit in kindergarten, we add these two pages to our TPR books. This shows an extension of the vocabulary.

This sample is a student who is working just at the beginning sound level. He later finished the sentence with assistance: “P(aper), t(ool), and rc (rock) are all nonliving things because they do not need food to survive.”

- Students read their TPR book to others.

As you can imagine, this is a LONG process. It takes weeks. We use the TPR throughout the entire unit, and often the TPR book is used as part of my assessment piece: Can my students recognize, produce, read, and write about our key vocabulary from the unit?

One of my favorite stories about TPR includes a student I will call Jack. Jack was a kindergartner who came from a Spanish-speaking family. He arrived in kindergarten already qualified for special education and speech services. He had very low verbal skills and some behavior concerns as well. It was very difficult to get Jack just to participate.

We were wrapping up our Living and Nonliving unit in kindergarten. Jack was putting together his TPR book. I was reading the page, leaving out the vocabulary words that I was curious if he picked up.

I said, “Listen to the clue: Living things ________, too. Young ones look like the old ones do.” Jack took his arms and swayed them back and forth as if cradling a baby, our gesture for the word “reproduce.” He then pointed to the coinciding picture. Although he could not verbally state the word “reproduce”, Jack had a sense of that word’s meaning, and he could participate in our task! My five-year old EL student with learning and speech difficulties was learning vocabulary and could express it! THAT is the power of TPR.

See page 81 in Teaching for Biliteracy for more information on TPR.

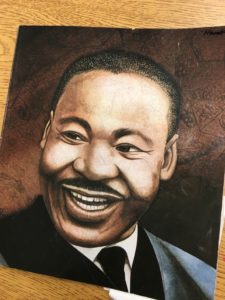

I have also started using Adapted Readers’ Theater (ART) with my class before I read a complex text. Most recently I did this with Martin’s Big Words by Doreen Rappaport. If you have not read this book, take a moment to do so. It is powerful and inspiring… and a bit over the heads of the average first grader. However, with proper planning for accessibility, your students can enjoy and relate to such quality texts.

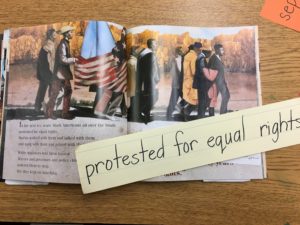

This is a sample from my MLK TPR, which I began with the class at the beginning of the unit. A lot of the words we preview in the TPR are also found in the book Martin’s Big Words. The background of the TPR was an essential foundation before beginning ART and before reading this text. The gesture clue at the bottom reads, “x with arms.”

I began by taking a picture walk through the book with my students, who were standing. On each page, I had planned to discuss a certain phrase and involve a gesture. The students, much like in TPR, were to copy the gesture. The phrase was then posted on the whiteboard.

We did this again the next day, reviewing each picture and now referring to the written phrases on the whiteboard (which were in order). At least half of the class remembered the gesture associated with the phrase when they saw the illustration. They helped each other through the book, and it was only their second time seeing these pictures.

On day three, I read the book. However, it wasn’t a normal read aloud. My students were standing, and I held the book in front, unable to gesture well because I was holding the text. My students brought the book alive! They helped one another remember the gestures for each illustration and this complicated text became comprehensible. We were then able to discuss the intensity of the illustrations, what it would feel like to be threatened, and how Martin’s Big Words continue to influence our world.

Try concept attainment, TPR, or Adapted Readers’ Theater with your class. These strategies bring vocabulary – and your students’ independence – to a whole new level.

Now when I get to unit-based read alouds (usually a few days after I have introduced and we have practiced the TPR), I am interrupted so often with text-to-world connections that I have to shut off the water! (Remember the fire hose analogy from my Oracy Development post?) The interactive read aloud experience becomes so valuable my students are chomping at the bit to have a moment to talk with their Thinking Partner about the texts at regular intervals throughout the reading. Saving unit-based read alouds until I have solidly set the foundation of vocabulary and context has significantly increased the value of the texts I share with my class.

Join me early May for the third Literacy Improvement Mini-series installment: Phonics: Dictado and the Bridge. In the meantime, I’d love to hear what strategies you use to enhance vocabulary access with your students!

About the Author: Dana Hardt

Comment (1)

Comments are closed.

This is a great way of teaching vocabulary. I will try some of the techniques you mentioned with my 8-year-old students.