Building Bridges between Alphabetic and Non-Alphabetic Languages: Looking Deep and Beyond Languages

In this blog, guest author Dr. Ying (Fiona) Du, Ph.D describes how the Bridge can be used effectively in Chinese-English dual language programs. Dr. Du currently works in a Dual Language Immersion elementary school in Richland One District, Columbia, South Carolina providing intervention services to students in small groups. She has fifteen years of experience teaching and coordinating Chinese-English dual language and, in this blog, will share some of her expertise with you. Dr. Du is passionate about making metalinguistic connections between these two languages in order to make biliteracy education successful for young learners.

Building Bridges between Alphabetic and Non-Alphabetic Languages: Looking Deep and Beyond Languages

The Bridge between languages is a vital part of a robust dual language program and of biliteracy instruction. The benefits of the Bridge are described in Ms. Beeman and Ms. Urow’s book Teaching for Biliteracy: Strengthening Bridges between Languages. As described in their text, the Bridge is an integral part of supporting students in reaching the goals of dual language: bilingualism and biliteracy, high academic achievement in both program languages, and socio-cultural competency (Howard, E., Lindholm-Leary, K.J., Rogers, D., Olague, N., Medina, J., Kennedy, B., Sugarman, J., Christian, D., 2018). The Bridge has two parts — the transfer of key academic vocabulary and phrases from one language to the other and the contrastive analysis between the two languages to develop the metalinguistic skills of developing bilinguals (Beeman & Urow, 2013).

Yet many teachers and administrators asked me, “How do you compare and contrast Chinese with English when the two languages are so different?” or, “How do you find similarities between Chinese and English when the two languages belong to different families and are looked at entirely differently?” They asked me the same questions before my presentation on this subject at La Cosecha Conference in November 2022.

The chart I created Areas of Contrastive Analysis between Chinese and English shared on Teacher-Created Resources page of the Teaching for Biliteracy website provides a summary of some major similarities and differences between the two languages. I have organized this summary according to the four areas of contrastive analysis described in Chapter 10 of Teaching for Biliteracy. (You can click here to access the document.) While these examples are useful for teachers planning for Bridge between Chinese and English, a new mindset to compare and contrast an alphabetic and non-alphabetic language and some practical strategies will help them identify the similarities and differences between the two languages and conduct the metalinguistic discussion with their students by themselves, using the vast resources of academic and social languages in their content areas. Hence the purpose of this article.

The Bridge is about guiding students in making connections between their two languages in order to enhance their bilingual development and to meet the goals of dual language education referenced above. Identifying similarities between the two languages will naturally serve this purpose well. Identifying similarities instead of differences is also the focus of this article. To find similarities between the two apparently entirely different languages like Chinese and English, one needs to step back, look beyond the physical appearances of the languages themselves, and focus on the rationality, mindsets and strategies that have created and will continue to create the two languages. The following are some of the concrete notions I used to find linguistic similarities between Chinese and English and I will also provide some examples of similarities within each linguistic domains listed below.

Logic, Rationality, Mechanism for Word Creation and Expansion

Morphology

Every language follows a certain logic in order to create its linguistic system. Chinese is a logogram—words represent meanings and sounds with “logo,” “picture” or “symbol.” English is a phonogram—words represent meanings by “letters” that stand for certain sounds. Despite of the apparent differences between the two linguistic systems, there is a parallel thinking in how words were created. The logic for Chinese is the “logo+sound” combination for more than 80% words where “logo” stands for meaning and “sound” stands for the phonetic of the word. The logic for English is “morpho-phonemic” where alphabetic spelling of words is chosen to represent both sound and meanings. However, the mechanism used for decoding the meanings of words and lexicon expansion is very similar. The Chinese semantic component logo, called radical (部首/偏旁) in Chinese, has a similar function as the word root, suffix, and prefix in English because all can be used repeatedly with another component to form new words. The radical for “water水,” for example, is three drops of water in vertical order “氵” deriving from the original drawing of flowing water. This radical has been combined with another component to form over 1000 new words–there are 1036 Chinese words with radical “氵” in a standard Chinese dictionary currently, each with a meaning related to water. When water is frozen, the liquid three drops of water becomes two drops of water “冫”which stands for “ice 冰”—there are 53 words with this radical listed in a current standard Chinese dictionary with meanings relating to “ice”. With the same mechanism, English uses root words, prefixes or suffixes to form new words. I found via Google over 100 English compound words with the root word “water” (waterlily, waterspout, waterproof), and there are certainly many more words formed with “water” and a prefix or suffix (watery or watering). English also includes over 240 words that include the root word “ice” currently.

I also found many English and Chinese words following the same morphological pattern to create new words. Here are some examples that teachers can find in their K-12 social and academic vocabulary repertoire easily.

computer (compute+er) 计算机 (计算+机)

teacher (teach+er) 教师 (教+师)

writer (write+er) 作者 (作+者

actor (act+or) 演员 (演+员)

classroom (class+room) 教室 (教+室)

playground (play+ground) 操场 (操+场)

hardware (hard+ware) 硬件 (硬+件)

software (soft+ware) 软件 (软+件)

television (tele+vision) 电视 (电+视)

birthday (birth+day) 生日 (生+日)

Phonology

Mandarin Chinese is a mono-syllabic languages with variations of four tones whereas English is a multi-syllabic language without tones. The differences are obvious to ears. However, many sounds of vowels and consonants are similar if not identical in both languages. The following is a table I recommend comparing these similar vowels and consonants in the two languages.

| Mandarin Chinese | English | |

| Vowels | / a / | / Õ/ (October) |

| / e / | / Ә/ (teacher) | |

| / i / | / Ẽ / (eagle) | |

| Consonants | / b /, /p / | / b /, / p / |

| / m /, / f / | / m /, / f / | |

| / d /, / t / | / d /, / t / | |

| / n /, / l / | / n /, / l / | |

| / g /, / k /, / h / | / g /, / k /, / h / | |

| / j /, / q /, / x / | / j /, / ch /, / sh / | |

| / r / | / r / |

The only two pairs of Mandarin fricative and retroflex I left out of the table are: / z /, / c /, / s / and / zh /, / ch /, / sh / have very distinctive Chinese sounds and do not sound quite similar to any of English equivalents than the sounds I listed above. I used Mandarin Chinese Pinyin symbols and American English phonetic symbols for phonetic notations in this table. For precise comparison and contrast of Mandarin Chinese and English pronunciations, please check this article and video (both in Chinese): https://c.wholeren.com/blog/869ab2e7ca; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=68HT9jn3qnM The English phonetic symbols used for comparison in the video is International Phonetic Symbols instead of American English Phonetic Symbols. Nevertheless, they do represent English pronunciation with very few exceptions of American English.

Syntax and Grammar

Measure Word is the hallmark of Chinese syntactic usage, and most people will regard this feature quite unique to Chinese language. However, a careful observation of the two languages will again reveal an area that shares a similarity. The following are the examples that English also uses measure words when counting of objects is emphasized and it even uses the same measure word with the Chinese ones. Here is another evidence of universal rationality at work within our languages.

one group of children 一群孩子

two pieces of paper 两张纸

three bottles of water 三瓶水

four boxes of chocolate 四盒巧克力

five bouquets of flowers 五束花

eight slices of pizza 八片披萨

a period of time 一段时间

two teams of football players 两队球员

Chinese and English do have many grammatical differences which I illustrated in my Contrastive Analysis Chart referenced above. However, I have also identified a few similarities. For example, I taught my elementary students about the Chinese “tag question.” I told them that when people want to be polite and indirect under certain circumstances, adding a short “tag question” could soften the tone of the whole question. When you are not sure if a classmate has taken your pencil, you can ask “你拿了我的铅笔, 是不是/是吗?” (You took my pencil, is it not/did you?) The tag question makes the entire question a little less accusatory and both Chinese and English use tag question for that purpose.

Pragmatics

People tend to focus on differences when it comes to comparing various aspects of cultures, including socio-linguistic aspects of languages. In reality, there are many similarities one can find between the pragmatic and cultural usages of two very different languages. Spanish, for example, has a similar circular and indirect discourse and narrative style as Chinese where both cultural norms prefer to let the readers draw their conclusions at the end of narration after all the details are presented rather than in the beginning topic sentence preferred by English discourse. (See Chapter 1, pp. 10-14 of Teaching for Biliteracy: Strengthening Bridges between Languages by Beeman & Urow for more information about discourse style.)

Above are just some examples of similarities in the four linguistic areas I identified after examining both Chinese and English with a new mindset. Discussing these similarities with my students have helped them connect the two very different languages with concrete linguistic materials. There are certainly many linguistic features more different than similar between these two languages, so how we teach these linguistic differences can make a huge difference for young biliterate learners. The following approaches could be effective to help learners develop metalinguistic understanding during the Bridge and Chinese literacy instruction.

From Concrete to Abstract, Make Real-World Connection, Track the Roots, Tell Stories

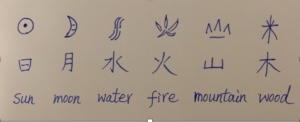

Just like teaching any other subject matter, making connections with concrete and real-world elements in our biliteracy classrooms will help our children understand and remember their languages better. Logographic languages like Chinese are fortunate in this aspect as the language has evolved from the original pictures and symbols representing the real-world elements which can provide clues to the meanings of the words. My illustration below shows how some of the basic Chinese characters have evolved into their more abstract modern versions from their originally representative drawings. Because they are visual and representative of real-world and concrete elements, it is quite easy for learners to comprehend and remember the meanings. Many Chinese teachers like me would teach this character etymology before introducing Chinese writing system because words like these are also used as radicals to form great amount of other words.

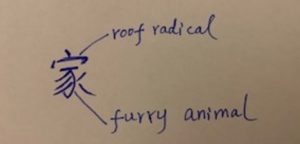

I consider the connection between the real-world elements and the little abstract modern versions of Chinese characters a rational instead of arbitrary feature of the language. Tracking the roots of words and telling the stories of characters can make the otherwise extremely tedious work of learning “arbitrary” characters viewed by layman much easier and enjoyable. The photo below shows the story of “家” (home) which I always tell my students—a roof on a furry animal is a home. They made immediate connection as they thought about their pets at home and the story helped them recognize (read) this character.

Although alphabetic languages like English do not have a pictographic feature, 90% of multi-syllabic words in English have Latin roots that can be dissected and analyzed (D. Eide, 2012). Analyzing word roots for meanings can help students’ spelling and vocabulary growth. For example, “ped” as in “pedestrian” means “foot.” So, a “pedestrian” is a person traveling by foot. Words with this root include: “pedal,” “peddler,” “pedometer,” etc. (D. Eide, 2012). Tracking the roots of English words also makes metalinguistic connections with Chinese or another second language as learners could see how both languages are created and evolved with logics and strategies, instead of “it just happened that way.” They would no longer just mechanically rememorize each word and complain how difficult it is to learn both languages.

If teachers explore, they could find some of the early English words also trying to make a shape-meaning connections with letters. Even though this linguistic feature no longer exists in contemporary English print text (unless with certain artistic touch), the logo-meaning feature in both Chinese and English could elicit leaners’ interest in studying and comparing the two languages. Such an interest could lead to their own metalinguistic discoveries of the two languages later.

Practical Strategies for Metalinguistic Analysis between Two Very Different Languages

All above approaches demand good amount of knowledge about both languages. I strongly encourage second language biliterate teachers to deepen the collaboration with their English partner teachers and never stop learning and exploring English language together. Below is a list of practical strategies for metalinguistic analysis I recommend:

- Become familiar with the linguistic features and history of both the non-English language and English

- Look for examples in the four areas: phonology, morphology, grammar and pragmatics

- Start with a similarity by looking for a pattern within one language and a similar pattern in the other language

- Tell the stories or background of words and expressions, e.g., sounds and images resemble elements of nature, to connect abstract written symbols to concrete aspects of the

- Use a T-chart to list as many examples as you can to build the connections for students

- Summarize the differences with patterns or regularities to make it easier for students to remember

References

Beeman, K., & Urow C. (2013) Teaching for Biliteracy: Strengthening Bridges between Languages. Philadelphia: Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing

Eide, D. (2012) Uncovering the Logic of English: A Common-Sense Approach to Reading. Spelling and Literacy. Rochester: Logic of English, Inc.

Howard, E., Lindholm-Leary, K.J., Rogers, D., Olague, N., Medina, J., Kennedy, B., Sugarman, J., Christian, D. (2018) Guiding Principles for Dual Language Education. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics

I also got some information about the definitions of several linguistic terminologies and examples from Google Translate look-up links.

The Bridge functions between the two program languages. Because many students enter dual language programs as simultaneous bilinguals, and because all students in dual language programs become developing bilinguals, we talk about building bridges between the two languages, rather than L1 & L2.

A Bridge has multiple steps and takes place over many days. Referring to a Bridge LESSON may make teachers think that an effective Bridge can happen in one 45-minute lesson.