A couple of FAQs…About the English Side!

Now more than every we are ridden with unanswerable questions. What happens next? How are my students? Can we do anything about this ever-widening gap? And most importantly, are all the people I love and care about going to stay well?

I hope you are well. There is so much uncertainty around us during this pandemic; I wanted to focus this month’s blog on some things that ARE answerable. So… What are the answers to some of the Frequently Asked Questions around Dual Language Education with regards to the ENGLISH-MEDIUM TEACHER?

I’ll focus on a few this time and chip away at some more in future blogs.

Here are the questions I will be tackling:

Q1: What do the units look like for English instruction in a dual language program?

Q2: What is the entire “Day Flow” for an English-Medium teacher in a TWDL program? (What are transitions like? Workshop model?)

Q3: How do I bridge from Spanish to English when I truly don’t know any of the words and get nervous about it always?

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

Q1: What do the units look like for English instruction in a dual language program?

A: What do the units look like for Spanish instruction in a dual language program? Here’s something important to remember about being the English-medium teacher in a dual language program:

The goals we have for our students are THE SAME as the goals ALL our Dual Language (DL) colleagues have for their students: bilingualism, biliteracy, and sociocultural competence.

The language of instruction does not change our goal, it simply defines for us which piece of the goal we, as teachers, are “in charge” of on the path to biliteracy. The content and language allocations of our school or district might say that I, as the English-medium first grade teacher, am teaching social studies, math, and English Language Arts to my first graders. However, the strategies, scaffolds, and supports I use to teach my students are the same as the strategies, scaffolds, and supports my Spanish-medium teacher colleague uses with the students when they are in her class. She, however, is teaching science and Spanish Language Arts.

I cannot do exactly the same thing as my monolingual classroom colleagues, because our goals are not the same. Their goals are to have their students read, write, listen, and speak proficiently in English. They have a curriculum to follow that was written with that goal in mind. I, however, have created my own curriculum after carefully mapping out the writing, reading, and content-area standards of our grade level with my Dual Language colleagues. We had to balance our literacy standards (never teaching the same main standards at the same time), plan for rigor on the diagonal, and support language development in both English and Spanish. Our units are integrated with content areas and language arts. I only have my students for half the day; there isn’t time to do an entire boxed reading curriculum separate from science or social studies, and, quite frankly, our standards (we are a Common Core State) call for literacy to be integrated across the content areas.

I recently read an article in Educational Leadership magazine. My favorite quote, not even directly related to dual language education, was around the characteristics of successful teaching practices:

“The most notable success occur in schools and districts whose teachers build their own, admittedly imperfect, curriculum.” (Educational Leadership, September 2019, p.32)

Feel free to read the full article here.

A boxed curriculum is not a better choice for our dual language students, even though it comes in English and our job involves teaching English. Standards-based curriculum integrating language arts and the content areas, when well-planned and written with developing bilinguals in mind, will serve our students’ unique needs.

ALL OF US in a dual language program, regardless of the language in which we teach, are language teachers. We must help our students build oracy before any reading or writing occurs in our integrated units. How do we do that? The same way other language-teaching colleagues do: through Total Physical Response, Adapted Reader’s Theater, concept attainment, or common experiences (see chapter 6, Building Background Knowledge in Teaching for Biliteracy for more on each of those concepts).

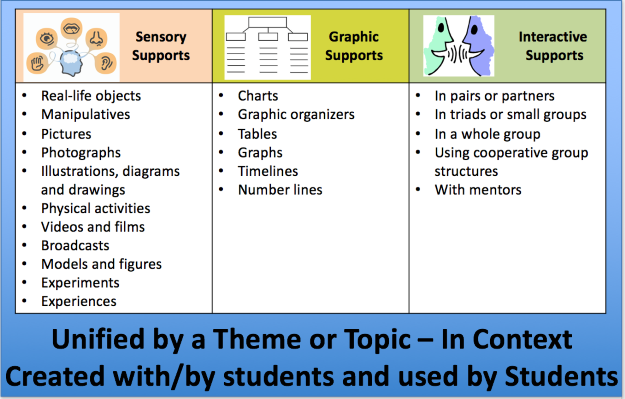

ALL language teachers must use graphic, interactive, and sensory supports for our students at every chance possible. Check out the great ideas for supports thanks to WIDA, adapted from the 2012 AMPLIFICATION OF The English Language Development Standards KINDERGARTEN–GRADE 12 (p. 11)

In short, all the units in a dual language program need to be written with the end goals of biliteracy, bilingualism, and sociocultural competence in mind, regardless of the language of instruction!

Q2: What is the entire “Day Flow” for an English-medium teacher in a TWDL program? (What are transitions like? Workshop model?)

A: What is the entire “Day Flow” for a Spanish-medium teacher in a TWDL program? I don’t mean to be redundant, but are you starting to get the picture? Replace “English-medium” with any other language: Urdu-medium, Mandarin-medium, Polish-medium… does the question still seem different?

The “Day Flow” depends greatly on the grade level you teach, how and when your school implements specialists (music, computers, library/media, PE if you’re lucky), recesses, and other interruptions or mandates. Working with your dual language colleagues to establish a daily schedule may make more sense than trying to collaborate with your monolingual classroom colleagues.

Because our curriculum is unique from monolingual curricula, so too is our daily schedule. The biliteracy units are written with oracy development FIRST, so what we spend a majority of our time on at the beginning of a unit is different than what we spend our time on at the end of a unit.

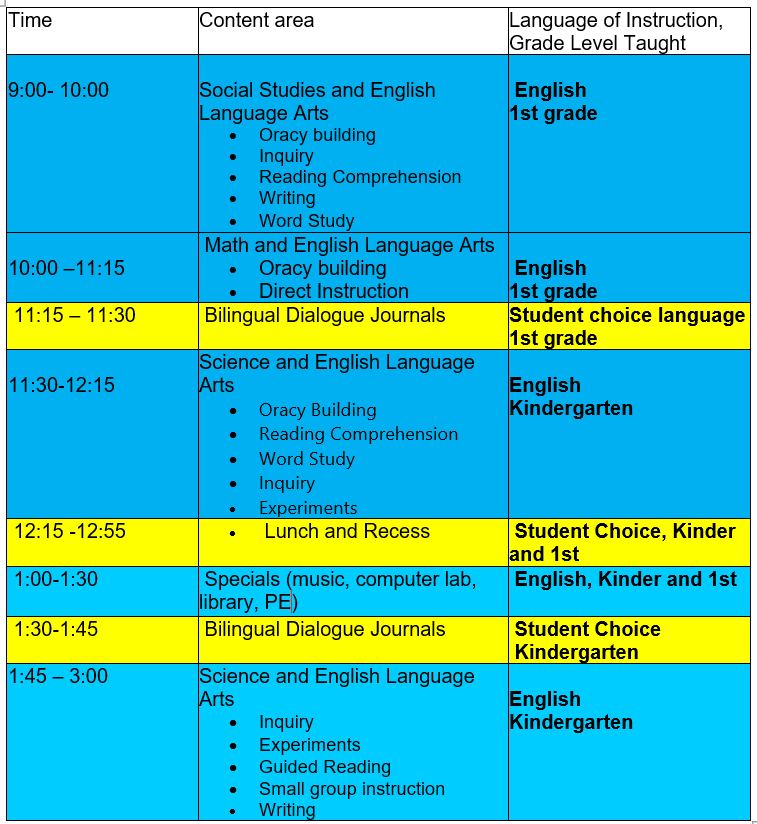

Here is the day from the teacher’s perspective in our 50/50 model. I teach first grade in the morning, when the kindergartners are with our Spanish-medium teacher, then switch midday and teach kindergarten in the afternoon. This is what the day looks like from MY perspective as the English-medium teacher:

Because I teach English, the language of instruction is BLUE all day, except for the times when my students have the choice of writing in English or Spanish in their Dialogue Journals.

If you teach two cohorts of the same grade level in a 50/50 model, the schedule would repeat morning to afternoon.

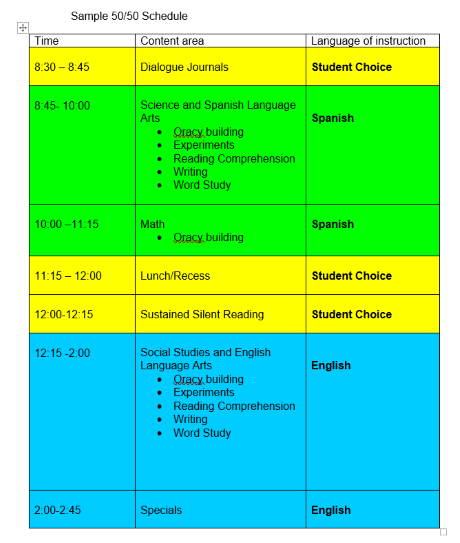

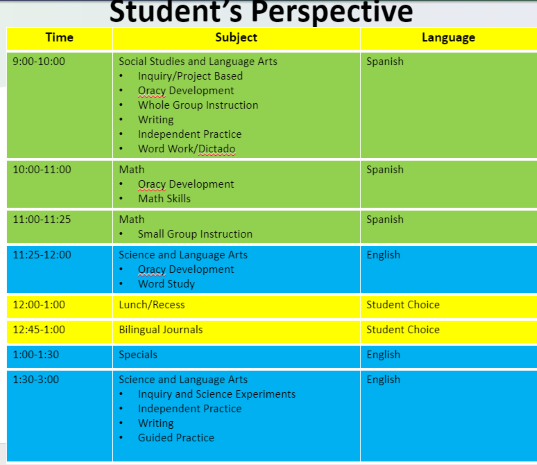

The daily schedule from the students’ perspective will vary depending on your content and language allocation, but here are a couple general examples:

This second schedule is how the day looks from the perspective of the kindergarten class in the program where I teach.

The chunks of time are general. While we attend to balanced literacy through the integrated unit, we won’t necessarily do, say, Shared Reading DAILY. So while particular elements of balanced literacy (shared reading, independent reading, guided reading, independent writing, shared writing, etc.) are listed as an example of something we may be doing during that chunk of time, we may not be doing each element every day.

It is important to work with your other-language partner to establish similar transition routines. When both classrooms mirror each other, pack up and line up routines, for example, give students a sense of security when they know what is expected regardless of the language environment.

A workshop model may work well at different stages of a biliteracy unit, but not all the time in a Dual Language program. We must first build oracy and background knowledge. Remember, too, that our units are integrated with literacy and content together. Is there really time for science inquiry, for example, if your students are confined to a literacy workshop model on a daily basis and you only have half a day with them? Remember what most models and curricula are designed for: monolingual instruction. You can read more about balanced literacy within teaching for biliteracy here.

Think of it this way: If you were training for an Ironman Triathlon (2.4 mile swim, 112 mile bike, 26.2 mile run), wouldn’t it make more sense to plan your training with other Ironman athletes? Or would it benefit you to talk with people who have solely run marathons? Their insights might be helpful for some of what you do, but their goals are different. Plan and schedule training with those who have similar goals and projected outcomes: “Ironman Triathletes”, a.k.a. Dual Language Educators! Your results will be better.

Q3: How do I bridge from Spanish to English when I truly don’t know any of the words and get nervous about it always?

A: I promise not to answer with a question on this one.

Full disclosure: I get nervous about it always, too.

But I’m lucky. I have a very supportive (language-teaching-centric) colleague (Bebi) to help me every step of the way. When it is time for the Spanish to English Bridge, we know we need to carve time out of our PLC or planning time for Dana’s Spanish Lesson.

First, Bebi teaches me her TPR. We go through it just like she does it with our students, except at adult speed. I literally repeat the actions and words and she gently corrects my pronunciation as needed. Once I think I have it, I go through it with her just observing. This is key.

At this point, I have practiced the words, seen them in writing, and associated a visual/picture as well as a gesture with each of them. We then work together to figure out the transfer to English. This is my chance to be gentle with her (Bebi is from Argentina. While she has lived in the US for over 15 years and has a certification for teaching English, she still considers herself a second language learner). We talk about the pragmatics of language and laugh and learn together. It is always interesting.

“Well, we wouldn’t say it that way in English. We’d say….”

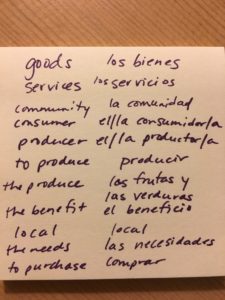

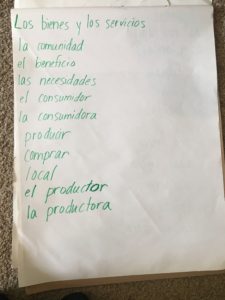

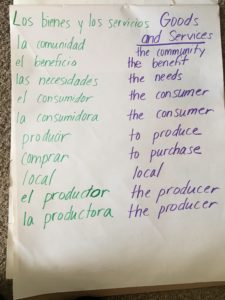

Here’s a sample of a cheat sheet I made to help with the transfer of our goods and services unit. I kept this by my side when the students and I wrote on the transfer chart.

We then decide on the words that we want the “children to come up with” for the transfer chart based off of the planned literacy extension, and I make my cheat sheet of the transfer so I don’t blow it and completely blank in front of the children. It used to happen before the cheat sheet.

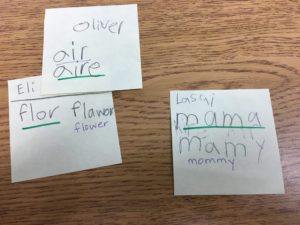

The next best part is what I get nervous for but always ends up okay: The children get to teach me!

Once they make their transfer chart with Bebi and it is passed to me, we start with reading the chart – in Spanish – together. I say, “Boys and Girls, I understand you have been learning about ____ (los insectos, las formas, etc.) with Señorita Yossen! Help me become more bilingual and say these words on your Bridge Transfer Chart.”

This is what the Bridge Transfer Chart looks like when it comes to me from Señorita Yossen and the students.

They read, I repeat. They LOVE correcting my mispronunciations and they LOVE helping me become more bilingual. It is empowering to them – and to me as well – to witness their confidence.

At this point, the students and I join together and I take the lead. We go through Bebi’s TPR, but this time in ENGLISH. They always light up when seeing the same images and doing the same gestures but with words in English. We move rather quickly because they do not need to learn the content again, just the associated words in English.

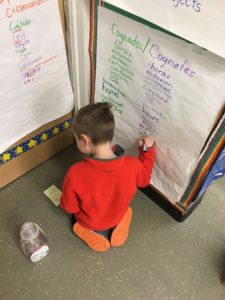

This is what the Bridge Transfer Chart looks like after we go through the TPR with English words and I add to it with the class. From this point, we can begin on our contrastive analysis!

We then go back to the transfer chart. They say the words in Spanish, I give them the English equivalent and they repeat it. Both times we say the words we do the corresponding gesture. And thus our Bridge study has begun.

I barely have to speak Spanish; instead, I empower my students to teach me. It is kind of like singing. I don’t feel comfortable hopping on stage to perform in the community musical, but I could sing all day in front of my class and know they don’t care when I miss a note or lyric. My Spanish is developing, but I still lack the confidence to speak with native speakers in the ways that I am willing to try in front of my students during a Bridge.

As for the contrastive analysis, Bebi and I always find something that I can grasp. Some of the more difficult contrastive analyses we leave for her Bridge from English to Spanish. Fortunately, we teach kinder and first grades, so our topics for contrastive analysis are based on Kinder and first grade standards in phonology, morphology, syntax, and

pragmatics. However, students often bring up examples for the Spanish side of the charts that I really do not know. In those cases, we simply write the idea on a Post-It note, and I check with Bebi later in the day. If approved, the students gets to add it to our analysis chart the next day.

In short, you don’t have to have a vast knowledge of Spanish to facilitate a Bridge well, but you do have to be a willing learner. Posing the transfer as an opportunity for your students to teach you is a solution that works well for me as well as the other English-medium teacher at our school (second/third grade).

I hope some of your questions have been answered! Feel free to leave more questions in the comments, and I will work to address them in a future blog. Until then, be well!

About the Author: Dana Hardt

Comments (3)

Comments are closed.

Thank you for sharing this information with us.

Dana! It’s like you read our minds! This is exactly the type of information our new TWDL teams needed. Thank you!

I’m so glad it is helpful, Amy! Please reach out with any other questions I may be able to help with!